TVU Networks announces a TVU Anywhere SDK, a free software development kit for the TVU Anywhere live IP video streaming app...

Search Words May Be Key, But Context Is King

By Paul Shen, TVU Networks

July 21st, 2020

Whether you are looking for a specific news article, the lyrics of a popular song, a technical manual or even this very blog, chances are good the author, an editor or web master has included metadata in the form of keywords to help search engines quickly and efficiently find your desired item.

It’s truly remarkable how quickly a search engine like Google will return the correct result for all types of searches, such as a recent one I did for “lyrics ‘Yesterday’.”

Not only do you get the first 15 lines or so of the lyrics, but there are still images from three YouTube videos linking to renditions of the songs with the lyrics superimposed. There’s result after result listing other sites with the lyrics, a link to the Wikipedia page on the song, another to the song’s meaning and even suggestions of other related questions people have asked.

Keyword Search Limitations

While many simply take it for granted that search results pop up on our screens in an instant, some of us are old enough to remember going to libraries, using the card catalog and browsing shelves for our desired book or article. To us, these online searches merit consideration for the list of modern world wonders.

Still, keyword searches have their limitations, especially when it comes to powering effective video searches that will enable the modern media supply chain to realize its potential of dramatically driving down the cost of a finished minute of video.

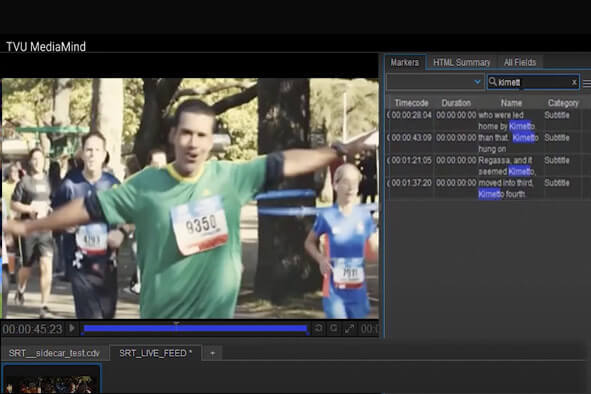

Closed captioning data generated with an AI algorithm and saved as metadata describing video frames is a good start when it comes to finding a desired video clip.

Contextual Searches

But that’s simply not enough. Keyword searches, while powerful, lack context –the very search characteristic that means the difference between unearthing the right footage in seconds and turning up many irrelevant results that take time and extra effort to review.

For example, imagine this hypothetical situation. An editor wants to find a clip of George Harrison saying, “Blimey, he’s always talking about that song. You’d think he was Beethoven or somebody” (as reported by Ray Coleman in his 1995 “Yesterday & Today”).

A keyword search for “’Yesterday,’” “The Beatles” “George Harrison,” “Paul McCartney” and the other words in the sentence might turn up a clip of McCartney talking about classical music, a clip of Ringo Starr telling John Lennon that Harrison said “Blimey, he’s always…” and a clip from a BBC documentary of British journalist Ian Hislop comparing the times in which both Beethoven and The Beatles composed.

Among the myriad other search results would likely be the actual clip of Harrison making his observation about McCartney, who was tweaking the song while on one of the soundstages used in shooting “Help!”

A contextual search of clips, however, uses the power of AI algorithms to hone in on the exact clip. A contextual search can leverage facial recognition and object recognition algorithms in combination with the keywords derived from a speech-to-text algorithm. Together, they would find the desired clip by searching for the words in the sentence, a match for Harrison’s facial characteristics and objects in the scene like the piano and mic on the soundstage.

It’s context that brings efficiency to this search, relieving an editor from taking minutes or even hours to review all of the hits from a keyword-only search, enabling the editor to be far more productive and ultimately allowing his media organization to produce more content that can be monetized.